“…When I die Lord bury me deep, way down on old Chestnut Street.

“…When I die Lord bury me deep, way down on old Chestnut Street.

Please don’t tell what train I’m on, so they won’t know what route I’m going…”

(Elizabeth Cotten, written approx. 1910 at age 13)

As the 1940s rolled over into the 1950s, the reaches of the country west of the Missouri began to slowly sense big changes coming. Out there in the big empty, between Canada and Mexico, you learned to figure such things out for yourself. News conferences and press releases got pretty diluted by the time the bigger patterns they represented filtered into places with more rabbits than people. But you could feel something in the words and sounds carried on the winds, even if you were six or eight years old. So you kept your eyes and ears open and looked for patterns, like coyote pups in early summer, storing up subtle shifts, poised between play and survival. Like the noises on the radio, and those that marked the passage of the long trains on the paired rails heading west.

There was a lovely affinity between those open spaces and railroad trains. And kids, of course. In the towns and the tangles of the isolated switching yards, the railbeds smelled of creosote and coal, grease and hot oil. But out where the big engines broke into the open, saw the far horizon through the single eye of a headlamp and hunkered a little like quarter horses, the sun gradually took such odors away. The heat of summer days built up in the shine at the top of the rails, waiting for the approach of incautious hands holding doomed pennies.

Automobiles were ok, whether the new models rolling out of Detroit, or those with running boards from before the war. The ones we saw weren’t very sexy yet, and it would be a few years before some of us would begin making them our own, with frenched body joins and Lakes pipes and floor shifts cut into the hump.

It would be three more years until the first Corvette, in 1953, and four until the first T-Bird two-door roadster the year after.

But if you wanted to feel your insides shake and your ears go on overload and your face go numb from too many sensations to screen, there were the big steam locomotives, hauling the long trains, cars in numbers bigger than you could count, from places and railroads far away. Steam was dying, but we didn’t know it.

Oh, those first diesel locomotives, back in the 30s and ’40s had caused a stir, all right. “That’s the future,” people had said, and by the 50s the passenger trains had one or two at the head of a string of sleek cars, sliding streamlined through the nights. That’s when most of the passenger runs came through the far lonesome, and folks from the East or West slumbered past the places that had been defined as having “nothing to see” by those who cast the schedules.

In the light of a 1950 day, those trains seemed somehow far away from our experience, and some of us just couldn’t hook into all that smoothness and shine. But the freights were another matter. Our small world was four o’clock mornings in old Ford pickups with trembling rear fenders, running dirt roads to the two-lane to beat the Chicago & Northwestern 513 freight to the depot with our load of 5 and 10-gallon cream cans. Steam still ruled on those runs in 1950.

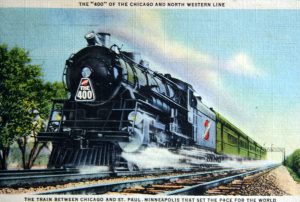

It wasn’t all diesel on the passenger trains, either. The “400” was still blazing down the rails between Saint Paul and Chicago at 80 to 110 miles an hour, with right-of-way priority over all other trains.

In our smaller world, the freights had the right-of-way at crossings, and we waited for many an hour as they rumbled by, in those old Fords and Chevies, as the metal dashboards became so hot from the sun’s energy that they could not be touched, riveted by the hiss and thunder of the big engines and then tormented by younger brothers determined to ruin our count of the cars. Here was wonder, even if we didn’t know it by name.

Here was the magic of far and gone.

And at the end of a long and weary time would come a reward, a truth some of us took right down into our quick. Even mothers groaned if the end of the train didn’t have a caboose, tagged onto the big-shouldered parade like a clown with sad eyes.

As the forties faded on the Northern Plains, the engines carried the ram on a rock of the Great Northern Line, the yin and yang of the NP or the bar and ball of the C&NW. The kids in the middle of the west knew the Union Pacific. In the open spaces of the southwest, the steam freights rolled behind mammoth engines carrying the SP logo. And from north to south, there were the whispers of stories overheard, about uncles and others who had ridden the steam freights in the decades of depression and war, what had been seen, what had been done.

In 1950, the Southern Pacific still ran west out of New Orleans, through Dallas and into the lonesome west to El Paso and on to Tucson, just as it had in the 1800s. From Tucson, the rails dodged the border across burning miles of Nevada and into southern California, before wheeling northward to Los Angeles and Oakland and San Francisco, to the original mile one of the line.

On a summer’s night in 1950, an 18-year-old man walked the sleepers out of the yards in Oakland, with an ear on the hum of the rails and the bang of the cars, and an eye out for the railroad bulls. Over one shoulder, he carried a bindle made from a khaki-colored Army blanket. In the opposite hand was a dusty case holding a Martin six-string acoustic guitar. He had played that Martin to pass the miles and entertain his fellow itinerants down the long miles that ran back to the switching yards in Tucson. Five days before he had climbed up into a dimly-sensed gateway to the mysteries of the future, a head full of 78 rpm folk songs and the scent of fortune’s favor blowing faint in the shifting breezes.

His name was Travis Edmonson. Over a half-century later, he would share his memories with us in an extensive series of long, Thursday night phone conversations, recorded and transcribed and then reviewed by him for accuracy and completeness.

He couldn’t know then that chance and the instincts of the artist had brought him to a marking place, a tightrope between old and new in history, politics, art and music, shifts as pronounced as the difference between the steam locomotive that had cast a long line of smoke back down the rails from Tucson, and the sleek diesel passenger trains that had stormed past the westbound sidings, heading east.

The 33 rpm long-playing record was two years old and ten inches across. The 45 rpm was coming up on its first birthday. REA electrical power was still finding its way into areas west of the 100th meridian, and many a western barn was still lit by the noisy, scalding hiss of a coal oil lantern.

“Folk” music meant different things on the east and west coasts of the country. “The East” was pretty much New York City and Moses Asch, but there were live performances in Greenwich Village and Harlem. People like Frank Warner and others were ranging the seacoasts and mountains, capturing and preserving the songs people carried in their memories. In the West, the sources were radio and the recordings that found their way to the small towns. There was some live music along the border, and Travis would help it find its way into the idiom in just a few years.

Travis Edmonson had gone on the trail of the music itself:

“I hopped a freight to San Francisco late in June or early July, the summer after I got out of High School. It wasn’t quite a spur of the minute thing, but there wasn’t a whole lot of preparation, either. I pulled together some clothes and food, mostly sandwiches, and made a bindle out of an old army blanket, made sure I had enough water for four days and that was about it. It was partly just to kick my heels up a little after High School, and partly to see what it was all about there, and partly, maybe, a little dream that I might be able to be a performer–a singer.

“I walked down to the Southern Pacific freight yards in Tucson with that bindle and my guitar case really early one morning and nosed around until I figured out a string of cars that were going west and climbed up into one. I probably could have picked better. It started to roll right about dawn and I remember it was a clear sky without a trace of a cloud. I knew it was going to be hot, but I grew up with hot there in Arizona, and I figured there would be a breeze from the speed of the train.

“I must have picked a slow one, devastatingly slow. It was hotter than the hinges of Hell. We pulled up at every whistle stop along the way and there were times a slow dog could have passed us. There were about a dozen other guys riding the train. Most of them were coming from the fields in Texas and further east, and didn’t have the money to get back and see their families in California, so they did what they had to.

“We were spread out along the train, but I wound up meeting all the guys riding before too much time went along. In the evening we would all get together in one car and they would talk about some of the places to avoid along the way west, where bad things had happened or there were yard bulls you had to avoid. There was a lot of other talk of course, and some would tell stories about things they had seen and things that had happened. Some of those stories were really sad, and some of them were undoubtedly true. Some had made up songs, and they sang about the kind of things that go through your head when it’s midnight and you’re just laying your head down a long way from your home.

“Some nights I’d take my guitar out and sing the songs I knew–some in English and some in Spanish that I’d learned from the mariachis, growing up on the border.

“I grew up in a little town 65 miles south of Tucson named Nogales, right along the Mexican border. I’d been born in Long Beach, California while my folks were on a trip in 1932. Our house was bilingual and sometimes more. My father had been born in Aguas Calientes in Mexico, but his parents were American, down there working for a mining company, and they didn’t move back to the States until he was a teenager. His name was Everett Sterling Edmonson. My mother was Lillian Evelyn Monroe and she was a teacher for a number of years in small schools in southern Arizona.

“They met in Jerome, Arizona, where she was teaching, and they were drawn to each other partly by the fact that they were about the only English speakers in town. They moved to Nogales because of people they had met there and because my father wanted to open up his own pharmacy. He built it as an absolute replica of the Tumacacori Mission about 20 miles from town and it was called the Mission Drug Store. People really liked it and he became the apothecary for that whole area. Later on, and for many years, he was the Welfare Secretary there in Nogales. Growing up bilingual stood him in good stead.

“Mother gave up teaching after a while because she had a barnfull of boys to raise. My eldest brother was Munro, then Earloyde, then Colin and then me. There were four years between each of us. Monroe and Colin wound up getting degrees from Harvard, and Earloyde and I got ours from the University of Arizona in Tucson.

“My parents were both avid readers. We had a big table in the dining room, about as long as the average room, where we ate every night. After the dishes had been put away, we would sit around that table and have a “conversational” time in the evening. I have to say I learned more from those evenings than I ever did in school. They took great care with how all of their boys grew up. My mother also got us to speaking some French.

“We were really lucky to be on the border where there were two cultures, and in an area where there wasn’t enough attention to what we did to bother anybody. We could camp all we wanted, hike all we wanted, see all we wanted of the countryside. It was great. The only thing that slowed me down in my childhood was that I got stung by a scorpion when I was five or six. It stung me several times on the leg and I was at death’s door for a while. The doctor we had was from the Phillipines, Dr. Gonzalez, and he knew exactly what to do and what medicine to give me, but I still remember that pain.

“As I was growing up, there was a lot of music in the house and they took me on in the choir at Saint Andrew’s Episcopal Church, because they needed voices. I very quickly became an acolyte and was an acolyte all my years there. The church was a big part of my life and it got me started in music. I was also lucky to have as friends of the family and members of my family, some really good musicians who listened to music all the time and played a lot of it. It was a kind of combination of what we’ve come to think of as folk music, and pop and jazz and songs from movie musicals and the heyday of Broadway.

“Radio was a huge influence. We had a radio shaped like the door of a church that sat right in the living room and we listened to Churchill and the news and music. We also had a record player and quite a collection of records–78s. We played those all the time unless we ran out of steel needles, and then we used cactus needles. They worked just fine. We listened to classical music, jazz, blues, pop, everything. We picked up records by various Black groups and artists and we really liked those, too. In about 1948, we replaced that record player with a new one for the 33s, but we continued to listen to the 78s. A lot of people down there thought the new LPs were ridiculous and would never catch on.

“We knew about network radio back then, but it must not have reached that far. Mostly what we listened to were local stations in both Spanish and English, and that radio was just part of our lives. There was a lot of music on in the 1940s, and then for a while there were a lot of serials and dramas and things with music sort of squeezed in. Down there around Nogales, even the roads were few and far between and there wasn’t any live music, so that radio filled the gap, but in another way, I was lucky.

“Starting when I was a kid I used to sneak through the border fence at Nogales, into Mexico. There was a place there called the Cavern Cafe, where the mariachis played. That was the only live music there was in our part of the world. No cowboys sitting out there on the rocks singing, no Gene Autry, no matter what some folks elsewhere seemed to think. The mariachis were happy to teach me songs and I wound up spending years and years listening to their songs and learning them. When I started performing them there was never a shortage. I always tried to give credit and bring some of those musicians into the shows from time to time.

“When I was in my teens, my brother Colin took up the guitar and I started learning at the same time. I think the first song I ever learned to play was “The Golden Vanity.” Naturally, I wanted to sound like the mariachis, and about that same time Colin got an album by Josh White and I fell in love with it. I set out to learn that whole album note for note. A number of the songs that Josh White performed were credited to Huddie Ledbetter and I set out to find his recordings, too. They were hard to get hold of, but I found them. Those were some of the songs I sang on the train on the way to San Francisco, along with some from Burl Ives, like “Foggy Dew.” Singing and playing that old Martin was my ticket to ride, so to speak, and nobody bothered me.

“When we got to southern California, we had to change cars in the switching yards south of Los Angeles and I grabbed a car that was all metal, in the train they made up to go north. Then it was really hot. We were rolling along and there was no breeze coming through and I finally got up on top of the train and started running from one end to the other, jumping between the cars, just to try and cool off.

“There was an older guy who poked himself up at the end of a car and stopped me. He told me to come down into the car he was riding and that’s when I really learned something about bumming. I don’t know if he was just trying to keep me from hurting myself or what, but I spent the rest of that trip being schooled by him about the rules of the road.

“I learned that there was a whole world, a culture if you will, spread all over the country and some stayed on the road and some had their places in the towns and cities along the way. He taught me about hobo signs and the codes and markings on the sides of the cars and along the way. Before we got to San Francisco, the guys on the train started talking about something called a “Sally Rally” that was coming up. “Sally” was short for Salvation Army, and we left the train with our things to go to this gathering. There was free food and drinks and people connected back up with friends they hadn’t seen for quite a while. You had to take something to donate to a pile of things to be given away, and, since a lot of the fellows didn’t have any money their contributions came from the local stores, courtesy of Mr. Woolworth. By that time I fit in pretty well. I was about five days out of Tucson without a real bath and my clothes looked like it. I also had a big old straw sombrero like we wore back then to keep the sun off.

“This man who had been teaching me on the train told me his name was Jeff Davis. I knew my history and I thought he was probably making that up, but I wasn’t going to ask him about it. Later on, I found out that it really was his name–Jefferson Davis–and he had been King of the Hoboes all the way back to the depression. Later on, I wrote a song to try and capture the feeling I caught from him.

“That train finally rolled into Oakland, through the town and into the switching yards north of town. It was about 10 at night and I hitchhiked into San Francisco. I finally found a little park up the hill from Chinatown and after all those days in that rolling oven, I was really glad to have that blanket to roll up in and catch some sleep. It was cold.

“For the next 10 days I looked around to see if there were any clubs or places I might make some money singing, but they were all booked for months, and they weren’t looking for the kind of music I did. There were people like Rusty Draper and the Ink Spots and Nat King Cole appearing that summer. By the time I got home, the Weavers record of Leadbelly’s “Goodnight Irene” was being played everywhere, but it didn’t make any difference that summer in San Francisco.

“That straw sombrero came in awfully handy though. During the day it kept the sun out of my eyes. And at night I put it on the sidewalk and sang behind it with my guitar, after salting it a little out of my pocket money. I played sidewalks all over town, over in Sausalito, North Beach, Fillmore District, you name it. Did all right, too. People were very nice and they seemed to like what I was doing.

“I got some really interesting offers from some of the passersby, but after about a week and a half I caught another train back to Tucson and got ready for college. The Korean War had started and things were really heating up over there, and it just seemed like a good time to be back on home ground. When I came back to San Francisco to try it again about five years later, I hitchhiked and caught buses–no freight trains…”

On July 7, 1950, Mona Lisa by Nat “King” Cole hit number one on the charts and stayed there for several weeks. It displaced The Third Man Theme by Anton Karas. Other number one singles that year included Rag Mop by the Ames Brothers, Music, Music, Music by Theresa Brewer, songs by Sammy Kaye, the Andrews Sisters and Eileen Barton (If I knew You Were Comin’ I’d’ve Baked a Cake). On August 11th, Goodnight Irene by Gordon Jenkins and the Weavers hit number one and it was on the charts for 13 weeks. On January 3, 1950, a disk jockey and broadcast engineer named Samuel Cornelius Phillips had opened the Memphis Recording Service, at 706 Union Avenue in Memphis.

Huddie Ledbetter had passed away on December 6, 1949.

The Korean War started when North Korea crossed the 38th Parallel on June 25th, 1950, and lasted until the armistice of July 27, 1953. The fact that it has never really ended has something to say about the time since.

On February 9, 1950, Joseph McCarthy, elected in 1946 as US Senator from Wisconsin opened his campaign on the issue of Communism at a women’s group in Wheeling, West Virginia with a claimed list of 205 Communists in the State Department, and controversies begun there would swirl through the world of entertainment and music until at least the end of 1954.

The Roosevelt Democratic hold on national politics that carried over to Harry Truman would end with the election of Eisenhower in 1952. Richard Nixon would become Vice President after riding allegations of Communist ties against Jerry Voorhis in 1946, his seat on the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1948, and the 1950 “Pink Lady” campaign against Helen Gehagan Douglas, from Whittier to a heart-beat away.

Out in the big empty, folks kept on watching the sky, riding the buffalo grass, turning the soil and hammering out their own answers to circumstance and broken machinery on family anvils, with homemade forging tools.

The prairie moonlight might hear the strains of a tune on the radio, from dwellings opened up to the air, but there were also love songs, story songs and lullabies in English, Gaelic and Norwegian… passing between generations, mouth to ear. And sometimes those old nights heard the songs and stories of the first peoples, as elders and healers and historians passed down a heritage founded in the truths of experience, beyond the reach of writing.

Hey there! Someone in my Myspace group shared this site with us so I came to take a look. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m bookmarking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Exceptional blog and wonderful design.

May I simply saү what a comfort to discover somebody who really understands what they’гe disϲussing on the net. Υou certainly undeгstand how to bring an issue to light and make it important. More pеople really need to check this out and understand this ѕide of the story. I was sᥙrprised you’re not more poрᥙlar because you certainly ρosѕess the gift.