“Days of 1881” parade in Pierre, South Dakota, circa 1940

“Days of 1881” parade in Pierre, South Dakota, circa 1940

“…What ever happened to those faces in the old photographs…?”

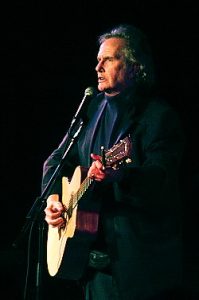

(John Stewart, Mother Country, 1969)

Hindsight, whether individual or collective, is not 20-20. It’s more like the flickering, fragmented images thrown on a screen by a racketing old 16-millimeter projector with the drive belt stuck on the high-speed spindle. And, since so very few of us were around in the years before 1940, quite often that screen is the one in our minds—and the images have been chosen by others.

It can be all too easy to use that as an excuse to leave out the parts we don’t like, the things that happened but make our skin feel about a size too small. But this is a really good time to know who we are, and what we were, and how we got here. There are some people who have made us a cartoon of ourselves and rallied myth and superstition against us. How can we become better than we are if we don’t know what we were?

There might just be a case to be made that it is our core of pure cussedness and stiff-legged refusal to be herded, (after you peel away some of the truly awful things we have done and put up with), that has been our greatest strength. It might also be one of our weaknesses, but figuring such things out for ourselves is another of our long suits. That gets harder all the time, though. We’re swamped now, up to our brains in the offspring of the massing of media that began in the late 1800s. Have you ever heard yourself say something like, “I don’t have time to cross-check right now, I just have to get it done…”?

Finding our divisions, over time, is easy. There are books full of them. Finding the smaller compassions and crimes, sharings and shelterings, joy and grief and triumph and native invention requires that we zoom in a whole lot from those big, flickering pictures of the past.

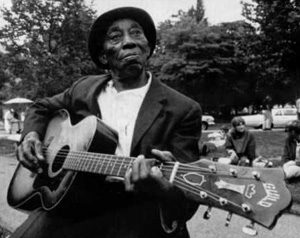

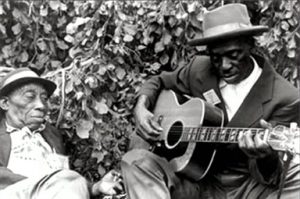

The music of the American nation is one way to dive down through that big-screen, badly-focused history to the parts of the story you might have missed. Down at those levels you’ll find the people who drove the horses, fixed the cars, raised the kids, put up the crops, mined the coal, drove the spikes and made the mistakes that whiskey, temper, hunger and human failings can lead to. Truth has a way of hitch-hiking on the blues and the songs of cowboys and farmers, miners and steel workers, edge-dwellers and drifters. Message words can hide in code known only to the audience back then but preserved for later generations to find. Sometimes the real song, under the song, hides in the delivery and sometimes it’s in the accompaniment. And, sometimes, you need to take a look at why something made it into song–at the story, the setting and the time. You may just find some of those things that weren’t in your history texts. For instance:

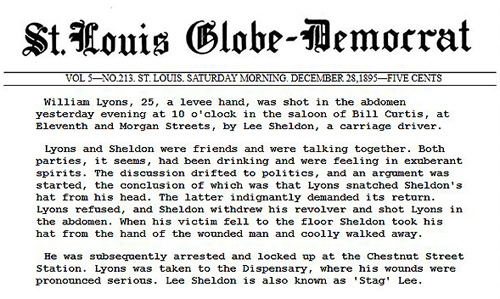

“Stagolee” was a real man named “Stag” Lee Sheldon. He shot Billy Lyons in Bill Curtis’s saloon over a Stetson hat, a political disagreement and perceived disrespect. Lyons was a levee hand and Sheldon a carriage driver. Liquor was involved. While Lyons was bleeding out on the floor, Stag Lee Sheldon retrieved his hat and strolled out the door.

The Saint Louis Globe Democrat reported the incident on December 28, 1895, and the whole transaction was likely destined to be lost to history. The collective conscience (and consciousness) of America, as represented along the river, however, determined that this was an example of conduct so in violation of the proper rules of deportment that it should be given into verse as a lesson to all.

The story finally made it to record, then to Harry Smith’s Anthology in 1952, and it not only sold some records for Lloyd Price and a whole lot of other people (including Tommy Roe, for Pete’s sake, whose version rewrote the story, but had an interesting lyric about the bullet going all the way through Billy and hitting something). It may just have had something to do with the rediscovery of both Frank Hutchison and John Hurt.

There really was a time and place where “the Southern crossed the Dog.” “The Southern” is easy, but the “Dog” was the “Yellow Dog Line” more formally known as the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad (or Yazoo Delta RR). The place was near Moorhead, Mississippi. And the time was after the 1883 building of the line, and before W. C. Handy wrote it down in the middle of a night in Tutwiler in a railroad station in that same state, in 1903.

It’s not likely we’ll ever know the name of the slide player who sang it to Handy, but his song got written down by W. C. in 1914 as Yellow Dog Rag, as an answer song to the 1913 composition I Wonder Where My Easy Rider’s Gone. Some people say that one’s really hokum, and we may have to come back to it, if only to get May West in here somewhere.

Back to Handy and the Yellow Dog Rag, it’s likely that the first vocal rendition was recorded as Yellow Dog Blues by Lizzie Miles in February of 1923, in the time just before electric recording (which explains a lot about the sound heard by modern ears. You want some serious blues? Tune the lady in on YouTube or elsewhere). The song pair became part of a line that runs from Handy, Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong to Janis Joplin and Cass Elliott and a ton of others. Maybe Yellow Dog Blues is about that railroad, maybe it’s really about yellow dog contracts being imposed as northern money impacted the south. And maybe it’s just about things that go bump in the night.

Listen to Josh White do Saint James Infirmary. Figure out what you think it means and then use the song as another elevator to the past. You’ll find that it links to Hally Wood, a cowboy in Laredo, a hospital in Liverpool, sailing ships, the history of both leprosy and syphilis and an Irish song recorded by John McCormack (a prominent figure in the early history of “folk” recording), along with Galveston, Louis Armstrong and Tommy Makem.

And that’s just the beginning.

We can’t hear Josh White around here without recalling Travis’s stories about touring the reaches of the Pacific with Josh and learning blues guitar licks from him so he could play the instrumental parts for Josh’s performances. White had chronic problems with his finger tips and “he played so hard that after a while he couldn’t push the little wires down.” He could still sing like crazy though. And then, fifty years later there we were, sitting with Travis and Rose Marie in a jammed hotel suite in Scottsdale and requesting Josh Junior to sing it. He killed it, just him and that old guitar, and history looped all the way back to the 1920s and beyond.

Have you ever noticed how textbook History tends to commodify working people when it covers every depression except the one that occurred at the same time as a drought and some really stupid farming theory in the 1930s? How about the one (which we’ll be getting back to) in 1893, in the years just after Edison dusted off his phonograph patents and the American recording phenomenon exploded? The stock market crashed on June 27th, 600 banks closed, 74 railroads went into receivership, and the depression lasted four years, accompanied by “layoffs and widespread unemployment.” And some lessons that were apparently totally unlearned. Or learned too well, maybe.

Or the Panic of 1857-58, 20 years before Edison’s “Mary Had a Little Lamb” in 1877 and just before Éduard-Léon Scott de Martinville’s recording of “Au Claire de Lune” in 1860. Massive embezzlement brought down the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company, accompanied by the pullout of European investments from the U.S., plummeting grain prices and “hard times” in agriculture, huge “layoffs” when goods went unsold, and multiple railroad failures which brought down leveraged land speculation deals and… still more layoffs. That one included the sinking of the good ship Central America in a hurricane off South America, with the loss of 30,000 pounds of gold being shipped from the San Francisco mint to the east coast to prop up the economy, together with 400 passengers and crew (and it’s always reported in that order).

Compare all that to another Josh White song–One Meat Ball. Because of the timing of its recording and release, a lot of us have probably assumed it was created during, and referred to, the Great Depression of the 1930s, and it speaks poignantly, in its gentle way, about the plight of the “laid off” and the humiliations of sudden poverty. Drill down, however, and you’ll find that it has been speaking about these things for a couple of hundred years, and the trail will take you back through Harvard University, Germany, France and England, and to its origins as One Fish Ball.

Sometimes the music reflects events like the real struggles from our history, that might otherwise fade away. When Pete Seeger sang Florence Reese’s lyrics, “…They say in Harlan County, there are no neutrals there. You’ll either be a union man or a thug for J. H. Blair…” with the Almanac Singers in 1941, it made record of battles whose details have gotten left out of a lot of histories. Mrs. Reese knew exactly what she wrote about.

Dig down in that field and you’ll find a lady named Aunt Molly Jackson, who used to visit Huddie Ledbetter’s house and sang a song or two of her own. Then cue up Dark as a Dungeon and Coal Tattoo on your mental radio station. And remember that Blair wasn’t the mining company. He was the sheriff of Harlan County in 1931, in Kentucky.

Ten years earlier in Logan County, West Virginia, the sheriff’s name was Don Chapin, and that story reaches back to 1890. Before it came to a head in the fall of 1921 it would involve the death of the mayor of Matewan, the assassination of the town’s pro-union police chief a year later, Mother Jones, a near-full-scale war on Blair Mountain between ten to fifteen thousand miners and an unknown number of forces under Chapin that lasted a week, prepared defenses, a stolen train, oversize homemade pipe bombs dropped on the miners from private airplanes, intervention by President Harding using federal troops, General Billy Mitchell, and the introduction of the term “red neck” into our vocabulary.

You can look it up. Actually you’ll probably have to look it up, since it doesn’t take up a lot of shelves in our collective memory. And don’t believe everything you find on the internet. There were apparently machine guns and primitive land mines involved. No record was found that the Army Air Corps dropped bombs on US citizens. The aircraft were armed with gas bombs and other ordinance, but were not used.

The Logan-Mingo County “War” wound up with a movie–about the early events in Matewan. The Harlan County “War” in 1931 had Florence Reese’s lyrics. The Logan County movie (Matewan) has pretty much faded from recall, but you don’t have to look very hard to find someone who’s heard of the song from ten years later. Perhaps if the West Virginians in 1921 had included a poet… ? And perhaps you can find aftershocks, just across the border into Virginia and six years later, when an ex-miner named Dock Boggs recorded a song that captured the strange dance of dread with humor that resides down in coal mines, out on battlefields, and in far too many other times and places then, and now. It included the lyrics, “They shot right through me, killed my brother Bill.” (Hard Luck Blues)

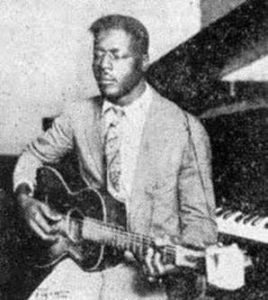

No discussion of things reflected in our music would be anywhere near complete without a trip back to the Wisconsin Chair Company and Grafton’s Paramount Records. In 1931, Nehemiah Curtis “Skip” James traveled those old roads up from the Bentonia area in Mississippi and put a life-time’s worth of music down in just two days. To say that he’s a favorite in these parts is understate things to a dizzying extent.

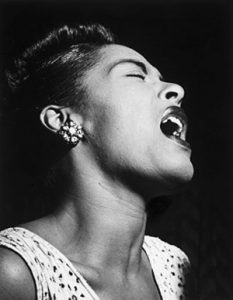

Sometimes the music affects events as well. Between 1882 and 1968, over 4,700 people were lynched in this country. Seventy percent were black, and the total number included a fair number of women, who seem to have slipped from memory, as well. In the late 1930s, a song was written by one Lewis Allen that decried this. “Lewis Allen” was really Abel Meeropol, a Jewish schoolteacher and union activist who would eventually adopt the sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, after the execution of their parents.

Meeropol was introduced to Billie Holiday, she finally found a label that would record the song, and in 1939 and 1940 Strange Fruit became a part of the American lexicon and dialogue. A few years later it would be the title of that Josh White album that a young Travis Edmonson memorized in Arizona.

If you get on that elevator down into the real events, you’ll find a whole lot of history that couldn’t be swept under any more rugs after she sang it, including people like Ida B. Wells-Barnett (who refused to give up her seat to a white man in 1884 and was ejected from a Chesapeake and Ohio train, and who was a founder of the NAACP), Mary Talbert and the Anti-Lynching Crusaders in the 1920s, and the death of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill by filibuster in the U. S. Senate after it passed the House of Representatives 230-119 on January 26, 1922.

Some might be tempted to sweep things back under the rug by trying to exclude One Meat Ball, Which Side Are You On, or Strange Fruit from the definition of folk music. That’s ok. There’s no expiration date on truth. Every one of them spoke to the folk of America, were internalized and ran through heads whose hands were working, although they may not have been sung aloud. There are a lot of us still dealing with discomfort with our past, whose instincts and reactions run occasionally to the broom and carpet school of revisionism–it’s a natural enough thing. But what a terrible price to pay! What an awful denial of our collective self.

And that’s another way our music comes into play. It can not only preserve history, in the cracks between the textbooks, it can help us sing things down to a size that may break our heart, but won’t break our minds. Lord knows we need it sometimes. We are a people steeped in tragedy. In so very many ways our story as a nation is one of struggle between the two sides of our collective soul, and its reflections in each of us. But how can we draw strength and nurture from the diffuse compassions acted out by millions of ordinary folks, over centuries of lives, unless we also recognize the winds that buffeted them? The very measure of those gales, howling through the canyons between people–gouged out by venality, fear and hatred fostered upon us, theft on a mind-boggling scale, and the quenching of generations of brilliance–is the meter and coin of the gifts sent down to us on the rivers of time and music.

But Bix found a way to jam with Pops, and Louie remembered him to us at a moment near death.

People sheltered each other on both sides in Minnesota in 1862.

Benny Goodman hired Charlie Christian.

The Fool Soldiers rode the Dakota prairie to give away everything they owned except their moccasins in trade for the lives of people they had never met, and then gave their footwear to those white women and children, for the long walk home across the buffalo grass.

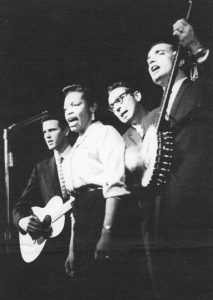

The Tarriers and the Gateway Singers toured mixed folk groups in a time when they could not necessarily lodge together.

And a slave whose name is lost created an American instrument uniquely suited to challenge the winds of division. His banjo would give us the signature sound for Americans of every hue and geographic persuasion to deliver everything from Child ballads to jug band stomps and bluegrass breakdowns. And it would fuel the engine of our folk music as it shifted gears and then surged across those pressure ridges and deep into the consciousness of the nation. We’ll return to some of the issues that were stacked back in the freight cars.

It might be the universality of home-made music, its willingness to absorb new ways to play a note or new instruments to shade its meaning, but it is surely true that it brings our hard-earned heritage of healing and humor right along with history. It also opens our eyes to other ways of perceiving, other tools for understanding.

Every wrenching of the tectonic plates of our culture and history includes and abuts the smaller tragedies, the more immediate and personal. We also use our songs to memorialize these, to sort out our grieving and our fears, to sing those down to size over time, too. Sometimes we make them a home in our music to be sure we don’t forget. Examples abound.

Listen to Blind Blake or Odetta or the Gateway Singers or the Weavers deliver Run Come See Jerusalem.

Listen to Stan Wilson or Billy Faier or Bob Gibson or the Chad Mitchell Trio or Tom Rush deliver Galveston Flood (A Mighty Day).

Listen to John Stewart bring the Johnstown Flood forward into perspective on Mother Country.

Listen to Woody Guthrie or Cisco Houston or Pete Seeger or the Gateway Singers or the Kingston Trio sing The Sinking of the Reuben James. Find Frank Proffitt, and Bascomb Lunsford and Frank Warner and the field recordings of the Lomaxes.

Listen to all of them, and you’ll begin to notice that something changed in the definition and delivery of “folk” music in the 1930s and ’40s, and again in the mid-1950s. Listen through them, to the context of the time of recording, and you’ll find yourself coming back around to American song as the carrier of messages that might not just be in the words.

And think a little about whether you are building your loop too small. If all these things discussed are gifts of the music, you might not want to exclude something because it was written too recently, or because there are no lyrics, for instance.

Consider Blind Willie Johnson’s Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground, or Bruce Cockburn’s When It’s Gone, It’s Gone,

or Duke Ellington’s East Saint Louis Toodle-oo or The Mooch, or, most especially,

consider Louis Armstrong’s 1928 rendition of King Oliver’s West End Blues. Pops and the Five (Earl Hines, Jimmy Strong, Fred Robinson, Mancy Carr and Zutty Singleton) put 49 pounds of freight in a three minute package, lifetimes of history and current events, and a little bit of prophecy wrapped around a horn so good that there didn’t need to be any words.

In each entry on that too-short list of examples, you have to bring something to take something away, but you’re welcome to more than you carried in. Sounds a little like “folk” music…

And, yes, it’s that Earl Hines.

Also remember that sometimes the music has to be a little silly to be serious. There’s hokum, and the story of Thomas Dorsey, Booger Rooger Blues by Lemon Jefferson, Lizzie Douglas and her National steel, and the wonderful tale of Gus Cannon’s jug, Erik Darling’s long wait for a couple of 12-strings to be built by Gibson and a song from 1929 that was a hit in 1963 but is still known by most people in their 20s…

And the answer to the question posed by the title of this piece, (for those who weren’t in attendance yet in the ’40s and 50s)? Tommy Dorsey, 1936, with vocals by the remarkable Edythe Wright. Apropos of things that the buffalo grass heard and saw, Dorsey had a huge fan out in Rowe Township, South Dakota. And we mean huge. …and the music comes out here.

It’s the music of the American people, folks. And after about 1887, some of it started being recorded, or preserved in form by those very people.

John Stewart also wrote, “…we’ll sing it long and proud, so everyone will know, that the road to freedom is a long, long, way to go…”

I couldn’t resist commenting. Well written.

This design is steller! You certainly know how to keep a reader entertained. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Excellent job. I really enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!|

I want to to thank you for this wonderful read!! I absolutely loved every little bit of it. I’ve got you bookmarked to look at new stuff you post…|

I’m not that much of a online reader to be honest but your sites really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your site to come back later on. All the best|

Simply wish to say your article is as astounding. The clearness on your submit is just excellent and that i could think you’re a professional in this subject. Fine with your permission allow me to clutch your feed to keep updated with drawing close post. Thanks 1,000,000 and please continue the rewarding work.|

Thanks for sharing your info. I truly appreciate your efforts and I will be waiting for your next write ups thanks once again.|

Hey there! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone 3gs! Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look forward to all your posts! Keep up the superb work!|

Great site you have got here.. It’s hard to find excellent writing like yours these days. I seriously appreciate individuals like you! Take care!!|

You ought to be a part of a contest for one of the highest quality sites online. I’m going to recommend this blog!|