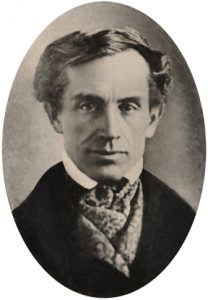

The “mechanical” side of American music and recording also had its roots in the 1700s. Samuel Finley Breese Morse did not invent the telegraph. He also didn’t invent Morse code. Born in 1791, he was an artist, a pretty well-known portrait painter, who also had interests in electricity, invention and politics. In 1817, he and his brother took out three patents relating to pumps. He founded the National Academy of Design in about 1825. In that same year he received a commission from New York City, to paint a portrait of Lafayette and, while working on it, a horse messenger brought a message from his father that his wife was “convalescent.” The following day he received another posting from his father that she had died. Although he left immediately for his home in New Haven, Connecticut she had already been buried by the time he could get there. It’s 81 miles from New York to New Haven. After this bitter experience, Morse set out to learn a whole lot more about communication over distances.

The telegraph had actually been invented 1n 1774 but wasn’t practical. It required that each receiver/transmitter be hooked together by 26 separate wires, one for each alphabet letter. By about 1832, two inventors in Germany had gotten it down to five wires.

In that same year, the story goes, Morse was on a ship back to the United States when he overheard a conversation about electromagnetism. It occurred to him that pulses of electricity could be sent over a single wire and used to send messages. Over the next five years, Morse built a working model. He employed home-made batteries, old clockwork gears and a couple of partners.

One was an academic named Leonard Gale.

The other brought skills at mechanics and his family’s iron works to the mix. His name was Alfred Vail.

By 1837, the first working model was demonstrated. It was still trying to send letters of the alphabet by tracing curves on a paper tape. It worked by employing a common dictionary at each end to encode and decode the curves back into letters. Within a year someone on Morse’s team had apparently decided to put meat back in the loop by substituting human fingers and ears for the tracing system, and let the machinery take care of the transmission of signals which made the code audible. Vail invented a code using dots and dashes for letters and numerals. Morse transmitted ten words per minute in New York in 1838. He was 47.

The foundation had been laid for the telephone and the speaking phonograph. And by the time those inventions were entering the market fifty years later, they would spin out the father of the vacuum tube, the grandfather of the transistor and the great-grandfather of both the home computer and the plug-in cartridge mayhem-generator.

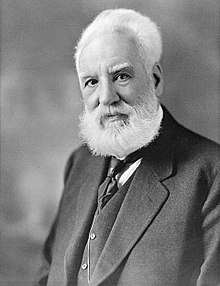

Alexander Graham Bell didn’t invent the telephone. He was an immigrant from Scotland, via Canada, arriving here in 1871 at the age of 24. While Morse had come at the problems of telegraphy from the direction of technology, specifically electricity, Bell came at them from the completely opposite direction. In many ways these two men show the present division between digital and analog approaches to problem-solving.

But the search for a device to transmit sounds leads back in time to Europe and one Jacob Reis. Reis took an approach similar to Bell’s, seeking a way to replicate the functioning of human anatomy. He began around 1850, when he was a teenager. One early experiment used a guitar case as a resonator, with a beer can as a mouthpiece and a sausage casing stretched across it as a diaphragm. The juxtaposition of beer, sausage and guitars is amusing, but Reis continued his quest for what he early called an “electrical eardrum.” Before he was done, he had begun calling it the “telephon,” and in October of 1861 he demonstrated the device before the Physical Society of Frankfurt, Germany by transmitting the verses of a song over a three-hundred-foot line. Demonstrations of improved technology continued until Reis died, broke, in 1874.

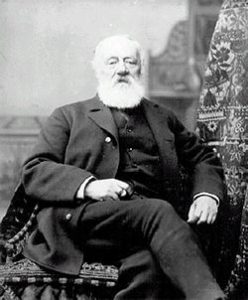

At about the same time as Reis was experimenting with guitar cases and beer cans in Germany, Antonio Meucci produced sound electrically in Italy. It was 1849. Bell was two years old, born in 1847. Meucci emigrated from Italy to Cuba, and then to Staten Island. In 1871, he filed a “caveat” or intention to file a patent for a device he called the “electrofono.” He apparently had three years to file the patent application for the device. During that time, he was caught in a steamboat explosion and spent a great deal of time near death. He never fully recovered, and the caveat expired two years before Bell filed his second patent application for the telephone. The time between filing of a caveat and a patent application would be 90 days by 1876.

Bell’s background was speech, hearing, sound and music. His mother was nearly deaf. His father had invented the first international phonetic alphabet. Bell was a gifted pianist, with a precise sense of pitch. He noted, while still at home in Scotland, that a note played loudly enough on one piano would sound the same string on another, that sound carried through the air could set up a precise sympathetic vibration on another instrument.

By 1871, back on telegraph track, the search was on for a way to carry multiple telegraphic messages down the same wire, to increase the size of the “pipe” down which messages were carried. It was a problem not dissimilar from modern bandwidth demands. Bell decided that the answer lay in varying the pitch of each message channel and set out to find ways to send signals down the wire at different pitches (or frequencies). In this search to improve the telegraph, Bell determined that a continuous, undulating current was the medium for the answer, rather than the interruptions of electrical current which drove the telegraph key. He would eventually figure out that the intervening steps and equipment could be eliminated, and the current could carry an analogue of speech itself, composed of varying pitches and complex waves.

Bell applied for his first patent (there were two involved) for the device which would become the telephone on March 6, 1875 and received it on April 6, 1975. It was for an “Improvement in Transmitters and Receivers for Electric Telegraphs.” It was assigned to Bell, Thomas Sanders and Gardiner Hubbard. The application called for use of a “vibratory circuit breaker,” and noted that while Bell preferred a “light lever of the first order,” other forms could be used including “membranes, etc.” The patent application doesn’t speak directly of speech transmission. Instead, it seems to propose a device we would call a facsimile transmitter and receiver, duplicating writing input at the originating point by a form of scanning device and using a stylus system at the receiving end.

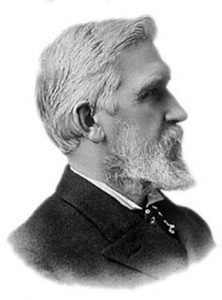

There was still another player. On February 14, 1876, Elisha Gray filed a caveat to patent a device called an apparatus “For Transmitting Vocal Sounds Telegraphically.” Two hours earlier, Bell had filed the second application—for patent of an “Improvement in Telegraphy.” This time, his was the only name on the application. Bell’s signature is dated as January 20, 1876. There were some lawyers about to get rich.

Elisha Gray was a farm boy from Ohio, who dropped out of school when his father died. He became a carpenter to support himself while completing preparatory school and two years of Oberlin College. He became fascinated with electricity and received a patent in 1867 for an improved telegraphic relay. He would eventually be granted some 70 patents. His 1876 patent caveat envisioned speaking and listening devices featuring a stretched diaphragm of a thin substance, and mechanisms for converting the vibrations of the diaphragm to electrical current and back, connected by a telegraph wire carrying a constantly varying resistance, in both frequency and amplitude.

The date of the first transmitted telephone message, “Watson come here, I want to see you,” would be March 10, 1876. It would later be found that Gray’s device, as described in the caveat, did in fact transmit voices and Bell’s device, as described, did not. It wouldn’t matter. Bell won the lawsuit. A lot of people over the years have read the opinion and come to the conclusion that the judge had given some pretty extraordinary consideration to Bell.

But Bell’s invention was really a “telephone” in name only. The wires swallowed the signal over any real length of line, and the diaphragm wasn’t producing a signal that made plain speech clear enough for the device to be really marketable..

Enter a true lost hero of American communication. A young immigrant named Emil Berliner invented a transformer capable of overcoming the voltage loss between telephone sets, and a carbon microphone transmitter for use in Bell’s device. Without them, mass marketing of the telephone would not have occurred at that time. He gave access to the rights to Mr. Bell. We’ll be getting back to Mr. Berliner.

He’s also the one who invented the phonograph as we know it.

1876 was the year of the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, and Bell demonstrated his invention there. By the following year, Bell had founded the Bell Telephone Company, and the first local exchange had been established in Hartford, Connecticut. In 1882, he took a controlling interest in a company called Western Electric, and in 1885 he founded the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, to deliver long-distance service. The Western Electric Company, by the way, had been started by one Elisha Gray.

When Bell’s patents came down in early March of 1876, he had just turned 29 years old.

And Edison turned 30 in 1877, when he was granted the patent that would, pretty much inexorably, lead us to Ike Turner and the Rocket 88. That’s another story, and we’ll tell as much as we know a little further down the line.