We have a great friend named Tom Barrett who has been a part of these discussions for any number of years now. He maintains that if we’re talking about folk, blues, jazz and country music and musicians, everybody and everything is connected to everything else, given some discrete number of iterations. The whole thing is like a pile of wire coat hangers.

But if you can’t identify the beginning that doesn’t preclude talking about some beginnings. One candidate for earliest American folk song, for instance, is On Springfield Mountain, a ballad recounting events in August, 1761 in the vicinity of Hampden, Massachusetts. A young man (22 years old) named Timothy Merrick set out to fill some of the long hours before his wedding by putting up some hay on his father’s place. Although snakes of the poisonous persuasion were, then and now, seldom seen in those parts, young Merrick entered a place in our history and song by succumbing to the strike of the rattlesnake in question. There were some possible embellishments to the story involving the possibility that Timothy’s intended, Sarah, was present, attempted to suck the poison out of her fiancé, and succumbed to a cavity in one of her teeth.

And a folk song occurred. By the 1940s there were at least two recognizable versions of it.

In keeping with the “pile of hangers” approach to tracking American popular music, sometime around 2008 we went out to breakfast with Billy Faier and the subject of On Springfield Mountain joined the discussion over eggs and sausage. Billy used to drive up from Texas once or twice a year to jam on the deck with the local Bloodliner faction (See John Stewart).

Billy Faier on the deck in 2007. The Great Assembly was recorded at a house concert later that evening.

— Click top arrow below to play introduction and history of the song.

— Bottom arrow for song.

— Back button to return.

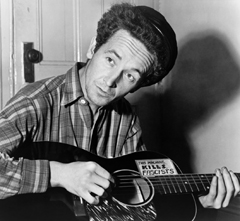

Billy was a banjo maven who was once introduced to a large crowd along the Hudson River by Pete Seeger as “the best banjo player I’ve ever heard.” We’ll return to Billy, but for now need only state that he was an integral part of the New York City folk scene in the early 1950s and hence, as performer, journalist, raconteur, sometime traveling companion of Woody Guthrie (“. . . just the one coast to coast trip, Gene . . .”) and hugely neglected folkmaster.

He talked about a third version of Springfield Mountain with reference made to Woody Guthrie and, we subsequently found it, recorded in the 1940s, re-released in 1989. He performed it right there while waiting for coffee refills. For a taste of the other versions of the song, we can turn to Burl Ives.

Sixty or seventy years after the unfortunate events in the hay meadow, there coalesced a peculiarly American form of entertainment called minstrelsy, or the minstrel show. It consisted of white people in blackface playing the roles of black people, so as to make them look ridiculous, through repartee, song and dance. Contrary to the easy assumption, minstrel shows originated in the Northeastern states, and by mid-century had been termed the “national art form.”

Over time, these blackface shows would be joined by African-American troupes, paving the way to the Blues.

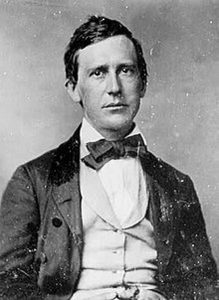

Another of the “beginnings” for the tangle of aesthetics and mechanics that lies under the phenomena of American recording is the “father of American music,” Stephen Foster.

Born in 1826, 65 years after the death of Timothy Merrick, Foster was only 37 when he fell in his hotel room in New York City, possibly as a result of a fever, cutting his neck and succumbing to the effects three days later at Bellevue Hospital.

He had, by then, authored a fistful of songs like Camptown Races, Old Folks at Home (Swanee River), My Old Kentucky Home, Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair, and many more. Contrary to another of those easy assumptions, Foster never lived in the South, visiting the region only once, on his honeymoon in 1852. In about 1850, he had signed a contract to provide music to the Christy Minstrels, the most popular of the minstrel shows, marking a pathway to modern folk music emphasized when Randy Sparks formed the New Christy Minstrels in 1961.

Those one and two-room schools sitting isolate on the reaches of the Northern Plains in the 1950s would coalesce into a county’s worth of kids two or three times a year. One was called “rally day,” an aggregate of individual competitions in track and field-like events. Another was “county chorus,” at which as many as a couple of hundred students from the tiny schools scattered over the county would convene to rehearse all day for a concert of American standards that night. That one-hour-or-so performance would inevitably feature several songs by Stephen Foster.

Off the plains, Foster would also prove to have more durability than the minstrelsy to which he contributed. By about 1920, there were a mere handful of troupes, as vaudeville, variety shows and musical comedies came to dominate the scene. Foster’s songs were anthologized by Nelson Eddy in 1947, and were recorded by Ray Charles, Jennifer Warnes, the Byrds and James Taylor, among others.