“…Put another nickel in, in the nickelodeon, all I want is lovin’ you and music! music! music…”(Stephan Weiss, Bernie Baum‚ Theresa Brewer, Dixieland All Stars 1950)

Why do movies have musical sound tracks? Why do television stories about the 1960s, always seem to have the same songs playing behind the same clips of Woodstock, Haight-Ashbury and throngs in protest?

Is it because the producers are looking for a foothold in our memory, and a common emotional response among the audience, to serve as a shortcut and foundation for the messages they are sending?

In a world as saturated by media as ours, it’s easy to lose track of some things. Like the fact that mass media as we know them have only been around for about a third of our national history. And that who we are, what we value and the choices we make as a people are a product of our individual experiences, set against our collective, accumulated memory of more than 500 years in this place and 300 as a country, but only a little over a hundred as a society with recordings of sound, and then pictures.

Print is different. Reading is, of necessity, another kind of interaction between our sensory apparatus and our brain. (Unless, of course, those stupid birds have begun to sing at 4:05 on the morning before a final, or you’re near an open school window in the last week of school. Then you can slide into that hazily conscious place in your head where your own internal movies are written by your hopes and fears.) Written words can certainly trigger memories and emotions, but not as effectively as smells and sounds. And music can amplify its effect by building on our cache of non-musical aural remembrances. If you experienced the sounds of steam locomotives, or train whistles in the night, or the cadence of freight cars hitting the join between rail lengths, there are beats and rhythms and themes that are going to take the fast lane into your cognition. You’re probably even going to hear the yodels of Jimmie Rodgers in a way different from those younger.

There is a huge body of literature out there about classical music, pop and jazz. When the term “American Basics” is used in this discussion, it is meant to draw a twisting line through the listening history of the country. That line follows the contours, the pressure ridges if you will, formed by the cultural fault lines developed over those 120 years or so of recording. On the more populated (and irrigated) side of the pressure ridges you find popular music (to include songs originating in musicals), classical performances, and some jazz. That’s also where the recording companies have historically been found, where the majority of the population was located after about 1917 (along with taller buildings and better footwear), and where the valves that mark the sources and destinations of the flow of American dollars have been most likely to turn up. The wages are a lot better on that side of the ridge, popularity more fleeting, and audiences further from the stage.

On the other side, it’s broken country and dockside bars, overalls and jeans, horse barns and red lights, weekly rents and flat tires, pint bottles and bus stops, work shoes and boots. It’s also blues, some jazz, old-time, country and “folk” music, and the occasional stray songs that got lost and stayed, like They Call the Wind Mariah. In the territory on that side of the ridges, the music can be painfully real, and real has had a tendency to find its way through the filters of the industry onto record. It’s where most of the attention here will be spent.

Sure, these are over-generalizations, but fault lines are, by their nature, buried deep. It can be useful to back off a ways and look for those pressure ridges. Think about it. Visualize a little. If the terms “parlor” music and “back porch” music are offered in the context of 1917 in America, on which side of the ridgelines do you think each was found in the days just before radio? Where did Fiddlin’ John Carson and Eck Robertson go to lay down their first sides? And where did the Lomaxes and Frank Warner and John Jacob Niles and Bascomb Lunsford go to find the source-springs of America’s musical basics?

To some extent it’s urban versus rural, but there have always been places in the cities that really should be mapped on the other side of the music’s ridgeline. People carry their music and memories to new places, and there has been a lot of that going on, for a long time. In 1860, 80 per cent of the 31 million Americans were rural, and there were 392 places with a population over 2,500 souls. In 1890, as the recording industry was being born, 65 percent of the 63 million people living in the U. S. were rural, and there were 1351 places over 2,500.

Gray states were urban in 1900, 40% of total population. Shaded areas were rural.

Gray states were urban in 1900, 40% of total population. Shaded areas were rural.

By 1900 there were still only eight states in which a majority of the residents lived in urban areas: Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Illinois and California. Residents in those states, however, made up 40% of the entire population of the country. It’s not that surprising that those same areas of the country would give birth to our mass media and be the heart of the recording industry as it emerged. It’s also easy to see why those concentrations would be the target markets for the record players, initially, and then the recordings to be produced once the industry figured out that it was dealing with an entertainment device, not a dictating machine. The kinds of recordings, and the artists who would be allowed to make them, would be largely based on decisions made in the northeast about what sort of product the people who lived there could be induced to purchase. The rest of the country would be along for the ride for a very long time.

The balance between urban and rural populations would shift in favor of the cities and towns just after World War I. It was just in time for radio to join the ranks of mass media, for the patents which had kept recording in the hands of the few to expire, and for the market for “hillbilly” and “race” records to be identified.

The musical names and legends in America’s attic of memories are the artists who made it through the industry’s screening to record at all, and the further thinning of the herd as recording companies decided what to actually press and release. Many of the fragile cylinders and platters upon which the songs of those survivors could be heard were destroyed by time, repetitive play and political and economic forces. There were millions of singers and musicians in this country before 1877 or 1890, and a lot of songs, both adopted and created. Some of them were preserved as sheet music, or even poetry, and some came down from mouth to ears. But the performances themselves, with all their nuance and setting, were lost to us, save for descriptions.

There were no recordings. After 1887, there were still very few artists recorded. We’ll simply never know what Buddy Bolden actually sounded like, for instance, even though many hold him to be the key figure in the origin of New Orleans jazz. If there were recordings they did not survive, although the melody of his (and Willie Cornish’s) “Funky Butt” was part of the published ragtime number “Saint Louis Tickle,” and was recorded by Jelly Roll Morton as “Buddy Bolden’s Blues.” Winton Marsalis was an Executive Producer for the movie “Bolden” based on his story, but the music of the man and his band is gone with the memories of those who heard and are themselves gone.

And the music is important, perhaps even vital, to us if we are to learn from the history of those in our American family who didn’t make it into any indexes, and a few who did. However, mediated by the recording industry that emerged, the recordings at the dawn of the “American Century” and since have both affected and reflected their times. And that means some of them are basic to us, if we are to have a realistic appreciation of our culture as it has emerged in the last 120 years, and to try to better understand the history that swirled around our ancestors and was made by them. The interplay of music, culture and history has been there for a terribly long while.

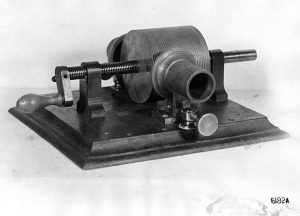

The music of a people has been a critical component of culture and preservation of their history for as long as there have been folks who had figured out the concepts of past, present and future. It was part of the conduit of remembrance for oral cultures. It lingered in that role after the birth of the written word. And that gizmo at the head of this chapter that looks like a cross between a nose hair trimmer and a tiny howitzer didn’t change that.

At some point, way back there at the start of the road, someone put percussion under the beat and rhythm of chant, and it became music. Whether you are striking a log, a drum, a string under tension or a set of those strings, you have begun to expand the reach of the mood accompanying the words. There are a lot of us who will never hear a slow, measured, muffled drumbeat again without returning to November of 1963 in our minds and memories, and we will not be light-hearted.

A few years ago, some of us were in Scottsdale, Arizona attending a celebration of the Kingston Trio and their songs. There were more guitars and banjoes there at once than most of us had ever seen outside a music store, and more players using them at the same time than the finale of a PBS fund raiser.

Down toward the end of it, Travis Edmonson borrowed a guitar and both participants and audience went quiet. Those days, this incredibly talented guitarist and gifted singer had only small use of his left hand. No one knew what was about to happen. He turned the guitar over, onto his lap, and used his right hand to set a beat, employing the guitar as a purely percussive instrument. He sang a song in the Yaqui language, as an elder of the small “tribe” assembled in that small auditorium. No one else in the venue could speak or understand a word of the song. It didn’t matter. Not only did the percussion accompany and expand the words, it allowed him to introduce tension into the performance by playing the rhythm of the song against the beat. And he set a mood of loss, of sadness and bittersweet memory, that several hundred people silently absorbed and radiated to each other and back to the stage. All without understanding a word.

Would his song have been as powerful if delivered a cappella? No. The accompanying music he made became part of the message, the mood and the memories. But there’s another very important thing to consider.

It wasn’t recorded, screened/”mediated”/influenced by interveners who could accept or reject it, pushed through patented recording technology, copyrighted, commodified, merchandised, marketed, purchased or reproduced in a home, car or set of earbuds.

It became, instead, a collective and composite memory for those who were there, to be filtered and played back against future learnings, subject to the emotional changes that recollection inevitably brings to human beings. His performance was stored and integrated in as many ways as there were people present. Their pieces of that larger memory included the heat outside in the night, the smell of the crowd, the sounds and hush, and whom they were with—what it felt like to be there—as well as the sound. It was all pretty much as if the year had been 1875 or earlier, if you add in electric lights, better shoes and air conditioning. And a whole bunch of Martin guitars and Vega banjoes. . .

When the last of us who were there that night have gone on, nothing will remain of his performance, save perhaps for these few words and the second-hand emotional memories passed on to our descendants by those of us able to tell the story in a way vivid enough for it to become part of that amorphous, individuated but cumulative thing we sometimes call the collective unconscious of the American People.

Now, if it had been performed to a specification and a prescribed set of emotions to be triggered, timed to limits, pattern-cut to the commercial desires of people who weren’t there, recorded and packaged in a manner meant to appeal to the largest audience, it could still become part of our collective emotional memory. But that’s a lot of filters. The prospects are better if the performer somehow made it to the recording booth through the side door of the studio, slipping through some of the holes in the screen.

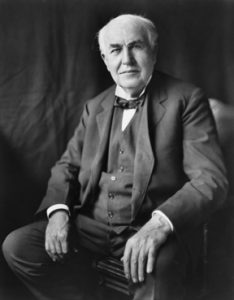

And that all goes back to a nursery rhyme, in 1877, probably between December 4th and 6th, but possibly in November. Thomas Edison produced a device called the “phonograph” and there was a patent issued on February 19, 1878 to prove it. There’s a lot of discussion to be had about whether Edison was the first to build such a recording machine, and the difference between a patent and a true working model, along with some names you may not have heard.

Before Edison, there were mechanical devices like water-powered organs, programmable automatic flute players, barrel organs, and music boxes. Player pianos, those wonderful machines for capturing and reproducing the individual finger strokes of geniuses like Scott Joplin and George Gershwin, would find a place American parlors. None of these devices captured “free range” sound out of the air.

It might be sufficient to note that the telegraph seems to have given birth to the telephone, and those two devices were parents to the phonograph.

But, in the background, there had been a fascinating thread of thought and invention that saw devices much akin to the phonograph posited and documented since the beginning of the 19th century, at least 70 years before Edison’s phonograph and 30 years prior to Morse’s first working model of the telegraph.

And there were “recordings” made 20 years before Edison’s patent, that would not be played back until over 130 years after they were created, finely nuanced tracings of a “ghost in the machine” and a musical treasure hunt worthy of a Nicholas Cage movie. Without the explosions.

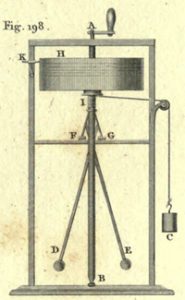

Let’s start in 1807, in Europe. Thomas Young was a startlingly intelligent Englishman, born in 1773. By his fourteenth birthday he had learned Greek and Latin and was acquainted with 11 more languages, in addition to his native tongue. By the time he was 23, he had earned a medical degree and by the age of 28 he was appointed a professor of natural philosophy at the Royal Institution. In the next two years he delivered 91 lectures covering a range of scientific disciplines that fully justified his appellation as a “polymath” and one of the most brilliant people of his time.

Those lectures were published 1n 1807 and included the description of a device called the “Vibrograph.” It was designed to measure the frequency of a tuning fork by attaching a stylus to the fork and using it to etch the vibrations from striking it onto a vertically mounted soot-covered cylinder. Speeds were regulated and the cylinder moved down against the stylus.

This thing begins to look like a recording apparatus from our viewpoint, without the ability to capture sound out of the air. With the keen acuity of hindsight, we could see this as the beginning of the base of knowledge that would lead to the phonograph (and eventually to the trunk of Ike Turner’s car). (We’ll get back to that one).

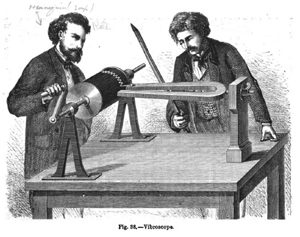

Across the English Channel and a little over 35 years later, in 1843, a French physicist and mathematician named Jean-Marie Duhamel took another step down this path and came up with a strikingly similar device, which he called a “Vibroscope.” Once again, the source of the sound waves to be recorded was a tuning fork. Once again, a stylus etched the wave form on a coated cylinder.

Interestingly, the cylinder was now in a horizontal position, as would be the case with Edison’s phonograph. Also interesting is the fact that that you can still purchase any number of modern “vibroscopes” today, designed to do pretty much the same thing—capture and document vibrations in critical environments like aircraft.

Nearly 150 years went by. And a series of discoveries would lead back to the 1850s and to sound recordings captured from thin air, 20 years before Edison’s phonograph. That story had somehow lain buried until 2008, when First Sounds, a collaborative of scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, figured out how to scan a paper “picture” of sound waves from April of 1860 and extract the audio represented. By 2014, one member, Patrick Feaster, went after the American history of the machine that “recorded” those sounds. He published his findings in 2016. Here’s the tale as we understand it.

There were 20 years and 70 miles between the Charles Banker collection of optical and auditory devices in Philadelphia in 1856, and the site in Menlo Park, New Jersey where Edison would found his research laboratory in 1876.

Charles Nicoll Banker was the president of the Franklin Insurance Company in Philadelphia and a very wealthy man. He had been born in 1777, well before the other players in this drama.

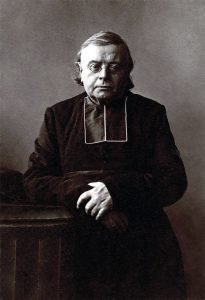

By the 1850’s Banker was accumulating a remarkable collection of optical and auditory devices, and was evidently reading Cosmos, a scientific journal founded in France in 1852 by Abbé Francois-Napoléon-Marie Moigno.

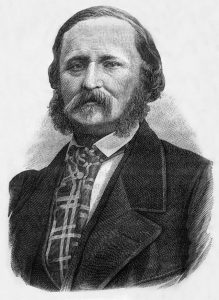

Also in France, Leon Scott (Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville) had been pursuing a means of recording sounds. A French printer, bookseller and inventor, born in 1817, he played a role in the development of stenography and wrote a history of the subject 1n 1849. While proofreading a textbook, he came across drawings of the ear and set out to render the functions in a mechanical device. He succeeded and patented the Phonautograph in France in 1857. He then came in contact with Moigno and his journal, resulting in exposure of his invention in both Europe and America

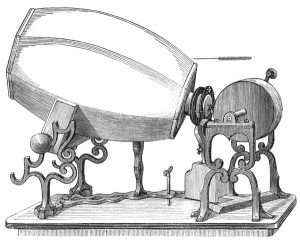

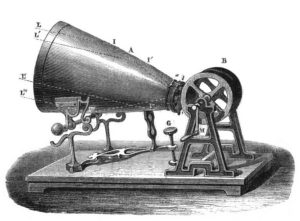

By 1858, The Journal of the Franklin Institute back in Philadelphia recounted an 1857 Cosmos article. Cosmos had described Scott’s device as consisting of a “tube” spreading out like a trumpet, with a membrane at the other end and a very light pencil attached in the middle of the membrane.

The “trumpet” concentrated sounds which entered it and the vibrations of the membrane were scribed on a paper coated with lamp-black that was passed under the pencil by clock-work. It was noted that the “traces thus produced may be copied and preserved (magnified if necessary) by photography.” The plaster of paris “trumpet” was soon replaced with one of zinc, in the actual trumpet shape we are more accustomed to seeing.

By 1859, Moigno would introduce Scott to a man named Rudolph Koenig, and those two would work together to bring the phonautograph to market. Koenig would launch a career as an independent manufacturer of scientific precision instruments, with his first catalogue, in that same year, containing two models of the phonautograph, for sale for 400 and 500 francs ($74 to $93 US).

Also in 1859, Moigno wrote in Cosmos, “The scientific passion that suddenly seizes wealthy American merchants presents a truly wonderful side. We are in frequent contact with Mr. Banker of Philadelphia, who has been taken by such a great love for optics that he would not forgive himself for letting a new device go by without immediately acquiring it.” (Banker was described as “an avid reader of Cosmos.”) Banker would also, apparently, show a keen interest in at least one acoustical device.

Whether Mr. Banker arranged a private purchase or ordered a phonautograph from Koenig’s catalogue is not known. It is pretty clear, however, that he had one of these devices no later than 1859, based on Scott’s own words written in 1878 that his device “has been in Philadelphia since 1859,” and the vanishingly small chance that it was anywhere but in Banker’s collection. There is substantial evidence that Banker’s phonautograph may have actually been the first manufactured by Koenig, since it had a “trumpet” formed from plaster of paris.

Charles Nicoll Banker died in 1869 and his collection was prepared for auction two years later. And that’s where that Nicholas Cage thing comes in, with Patrick Feaster in the role of the intrepid explorer.

Feaster tracked the disposition of the Banker collection, and the whereabouts of the phonautograph that had been included in that collection in Philadelphia in 1859, with persistence and attention to detail that are simply remarkable. We may come back to that story in greater detail later in these pages, but for now we’re unable to resist referencing in a couple of documents he discovered, and which clearly indicate that the preceding saga is not just an audiophile’s fever dream.

Call it the department of “Ok, I can accept that this thing was in Europe, and that’s pretty cool, but show me the proof it was being used here in America way before Edison’s phonograph. Hmmm. . .?”

Well, Feaster found that the auction item listing of the Banker collection still existed in two places, in part by searching WorldCat, a catalogue that itemizes the collections of 15,600 libraries in 107 countries, whose roots go back to 1967. You can find those two references HERE.

He followed the trail of the catalogues and hit paydirt in Canada. He located the single available copy of the auction listing of Banker’s collection. It is simply incredible, comprising some 42 pages of dense item lists. You can lose a couple of days just scrolling around in it. Or you could look HERE and use the page finder to look up the items listed under lot number 630, on page 38 of the .pdf file.

Feaster would pursue the phonautograph and paper “recordings” made on it to the Stevens Institute (of Technology) in Hoboken, New Jersey. Time will tell if the device itself will ever be found in the numerous locations of the huge collection there. We’re pretty sure that if it appears it will be reported by First Sounds and Patrick Feaster.

In the meantime, as noted earlier, these folks found a way to translate the undulating analog waveforms inscribed in those phonautograms into digital signals, not unlike the WAVE files familiar to those of us who have captured recorded music to computer files. This is an image of a phonautogram from 1859.

![]()

And THIS (at :47 – wait for it ((and don’t mind the material at the end)) is the sound of what is generally held to be the first known voice recording, captured from a paper phonautogram waveform by the folks at First Sounds. The mathematics behind that spectral voice would later be recalculated and more accurately reproduced. It’s the baritone voice of Scott himself, according to those knowing much more than us. But this is the sound we originally encountered, before the recalculation. And this is the one that has stuck in our mind’s ear, like the plaintive call of history’s ghosts.

One could get lost in further details of discovery and process, but it’s time to zoom our attention back out nearly 20 years, to the wider view in 1877, and ask a couple of important questions about Edison’s phonograph. Not what we mean by the word, but what did he mean by “phonograph?” And what did a nursery rhyme have to do with anything? For answers we return to Menlo Park.

Edison had been working on improvements to the telegraph as well as to the telephone Bell had patented the year before, in 1876. In 1877, he was working on a machine to bring greater efficiency to the dissemination of telegraphic messages, by recording the message on indentations in a paper tape, so it could then be retransmitted repeatedly. Being who he was, it’s hardly surprising that he would come up with the notion that perhaps the same thing could be done with telephone messages.

One thing led to another, paper became a cylinder of tin foil and a guy named John Kreusi invested his mechanical skills, Edison’s sketches and (supposedly) 30 hours of hard work. He came up with a gizmo that put grooves in the tinfoil with one diaphragm-driven stylus and played them back with another. The styluses moved up and down in relation to the surface of the cylinder, which would prove to be very important, later.

Edison was also a practical man. If you have a device that can capture a spoken voice and then play it back somewhere else, you need a market for people who want such a thing, and have the money to buy one. So, while the patent was pending, he demonstrated it in the offices of Scientific American, formed a company, and came up with a list of uses for the thing. The primary use he envisioned, and number one on his list, was “Letter writing and all kinds of dictation without the aid of a stenographer.” This intended use for the machine was also included in the name of the company.

If we go back to the Greek roots of the words for “writing sound” we get phono and graph (and gramo and phone and grapho and phone). The name of the company was the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company. The device was a hit. Demonstrations were given, and publicity was generated, but it was hard to operate, and the tinfoil gave out quickly, which meant, of course, just as you were dictating something like “My Dear Mr. Westinghouse, I find your offer regarding electricity SKRCH…”

Once the novelty appeal had worn off, interest waned, and Edison got caught up in the development of the incandescent light bulb. Speaking of electricity, by 1882, Edison was using direct current to light up Pearl Street in Manhattan and by 1887, there were 121 Edison power stations generating DC for customers. 1887 was also the year that a young chap named Nicola Tesla filed for seven U.S. patents that comprised a complete electrical generation and transmission system, as well as motors and lighting to use it, employing alternating current. We’ll be coming back to 1887.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Leave Edison’s little machine gathering dust for 10 years on a figurative back shelf in his lab. Twenty years and 28 miles away, at the Stevens Institute in Hoboken, the first instrument designed to record sounds out of the air was in all probability also gathering dust.

And the rhyme was “Mary had a little lamb,” the first words to go into and be reproduced from Edison’s first speaking phonograph. . . in 1877.